The National Restaurant Association Show in Chicago brought together experts and executives from across the industry to discuss the latest hospitality trends, ranging from artificial intelligence to a return to on-premise dining. But there were some questions that went unanswered, at least to the satisfaction of Restaurant Dive.

Here are three questions Restaurant Dive has been mulling over since we left Chicago.

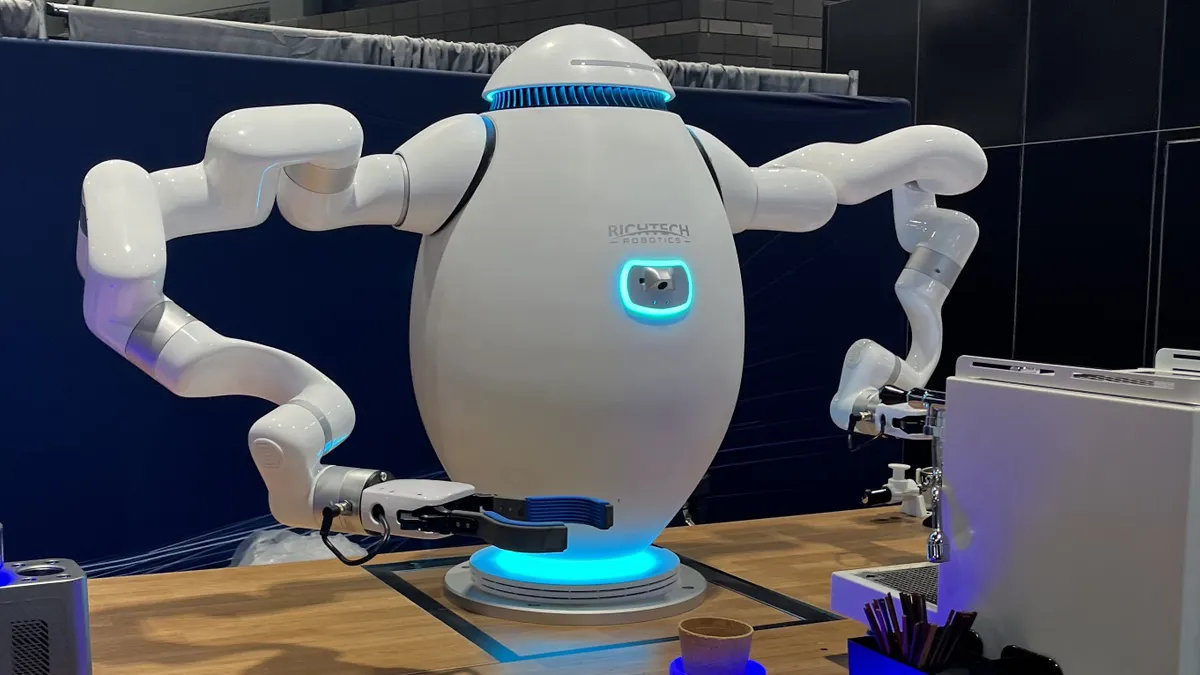

There are robots at NRA, but why don’t we see more in restaurants?

From servers to robotic fry cooks and automated baristas, the NRA show floor, as always, was replete with new tech that promised to save labor.

Yet, aside from instances when Restaurant Dive has sought them out, restaurant robots still seem rare in the wild. But there is also scale to contend with — there are, after all, around 724,000 restaurants in America, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As early as 2010 — 15 years ago — The New York Times profiled robots as if they were poised to take jobs in the industry. Yet in 2025, there are several million more restaurant workers than in 2010, and nominal wages are higher than ever.

Some full-service dining players, like Bruce Nelson, a fractional CFO across several restaurant groups in Minnesota, think that AI could work in the back of house to analyze data. But major use of robots to serve customers runs counter to the ethos of hospitality, Nelson contends.

“When it comes right down to it, we are a human business, and we always will be a human business,” Nelson said. “I don't want to go to a restaurant and have a robot feed me.”

An answer to the question might come from the robots themselves, and their developers. Richtech Robotics, now on its fourth NRA show, showed off a new version of the company’s barista bot, Adam.

“Train me once and I can craft coffee, shakes, cocktails, make boba tea, grill burgers, cook noodles or [do] any countertop task you ask of me,” Richtech’s robot intoned at its booth.

But Adam costs $3,500 a month for “robot-as-a-service,” according to Timothy Tanksley, Richtech’s director of marketing. The average production and nonsupervisory restaurant worker earned $19.19 per hour in February, according to the BLS.

Adam would have to operate 182.3 hours a month — 42 hours a week — for its monthly cost to equal the labor cost of a worker.

That assumes a robot is a one-to-one replacement for a worker, and that it costs nothing to install. Yet Adam, per Tanksley, is meant to function alongside baristas, not replace them.

“As soon as an order comes in, he's making it, he's sending it out, that kind of thing. And that really allows the humans to talk to guests,” Tanksley said.

Major brands are signaling that winning price-sensitive consumers depends on convincing them to treat cafes as places to hang out and socialize, with baristas as well as customers. Does it make sense to hire the equivalent of a full-time employee just to make it so existing employees can talk with consumers a bit more? If not, where does a robot fit in?

Maybe nowhere. Richtech’s Adam is deployed in fewer than 10 coffee shops and a handful of Walmart units across the U.S.

Is a recession around the corner?

The biggest question at the show was also one nobody could answer definitively. What is the macro outlook for the economy?

Traffic is down, but not by much, said Victor Fernandez, chief insights officer at Black Box Intelligence. David Portalatin, Circana’s senior vice president and industry advisor for food and foodservice, echoed this sentiment. Both cautioned that this is a continuation of previous trends — if tariffs are going to have a serious negative impact, it hasn’t shown up yet.

Or maybe traffic isn’t down at all — for some restaurants, at least. Both Jonathan Gillespie, a partner at Chicago fine dining restaurant Adalina, and Nelson, said their concepts have either seen recovery after a drop in the winter, or they outright haven’t seen traffic fall.

“Restaurants are the canary in the coal mine,” Nelson said. Restaurants are highly discretionary, after all — the consumer can always eat at home.

And so far, the data is noisy. Earnings season bore this out. Many brands saw traffic fall, but some saw shocking surges, and others — including Starbucks — saw their losses shrink. With tariffs starting to bite and more potentially on the table, we may have an answer sooner rather than later.

Can the mocktail replace the cocktail?

Gen Z consumers are likely drinking less alcohol. Good for society? Maybe. Good for restaurants? Probably not — alcohol is a high-margin, high-price good.

If consumers aren’t pulling back from liquor out of health concerns, they may be doing so to manage their spending, Fernandez said.

About a quarter of companies Fernandez works with say they’re seeing guests skip alcohol, or beverages altogether, in the current macro environment.

Nonalcoholic beverages are filling the gap, somewhat. Nelson said restaurants he works with are offering non-alcoholic cocktails for a $6 or $8 price point, while an alcoholic drink costs roughly twice that.

Many consumers, especially Gen Z, are willing to shell out for beverages, to the point that afternoon beverages are an emergent occasion. McDonald’s is looking to capture some of that interest with its forthcoming beverage tests. Still, sugary iced coffee and refreshers loaded with boba may fulfill a different need than mocktails.

In many markets, consumers may be paying at parity for non-alcoholic drinks, said Casey Gamblin, area beverage manager at Ithaka Hospitality Partners.

“NA beverage pairings versus spirit forward beverage pairings are being priced exactly the same, I'm seeing that in cities like here in Chicago and New York City, LA,” Gamblin said.

Some consumers are certainly willing to pay $14 for a glass of bitters, soda water and botanicals. But how many? And for how long? And will the humble club soda with lemon, ordered from an obliging bartender, remain an appealing option for sober consumers who still want to fit in at bars and restaurants?