This article is the second in a three-part series focusing on the impact the lack of additional grants from Restaurant Revitalization Fund has had on the restaurant industry, including a profile of Chef Greg Leon's pandemic story and reactions from across the industry to the Senate's inability to pass a refill bill.

A grandfather’s prized silver dime collection, lovingly set aside in the hopes of passing it on to future generations. A family home in Nevada. A string of struggling restaurant locations put on the market by an operator at the end of his rope, only to be snapped up by larger, more monied franchises.

These are just a few examples of what one year without the Restaurant Revitalization Fund has cost restaurants fighting to survive, Erika Polmar, executive director of the Independent Restaurant Coalition, said.

The $28.6 billion federal grant fund ran dry in just three weeks, closing on May 24, 2021. Last week, a bill that would refill RRF with $40 billion — legislation the IRC and countless operators were “belligerently optimistic” about — failed to pass the Senate. Now, it seems that nearly 200,000 RRF applicants who were approved for grants but didn’t receive them may never see that money.

“When Congress offered these restaurants the RRF lifeline, restaurant owners and operators made business decisions based on those commitments. Restaurants that are still trying to make up for what was lost in the pandemic today are struggling with workforce shortages, record-high inflation, and supply chain constraint,” Michelle Korsmo, president and CEO of the National Restaurant Association, said in a statement last week. “[The Senate’s] vote will further exacerbate those challenges and result in more economic hardships for the families and communities across the country that rely on the restaurant and foodservice industry.”

The disappearance of RRF’s safety net plunged many struggling restaurants deeper into financial danger over the past 12 months, but it has also wreaked havoc on operators emotionally, Polmar said.

Polmar continued, “It's been two years of not knowing how you're going to survive and how you're going to keep your people employed. … It's been awful.”

That fear has been compounded by the uneven playing field left in RRF’s wake. Restaurants that received grants have a leg up over operators still struggling to crawl out from under debt accrued during the peak of the pandemic, which has amassed like layers of “compounding grief,” Polmar said. This grant money has helped the lucky few raise wages to attract and retain better talent, or invest in remodels or expansion.

“There’s [been] aggregation of assets through the entire pandemic. The rich got richer, the poor didn’t. And I think you see that in this industry as well,” Polmar said.

Without a refill, she doesn’t see how the industry can reach true recovery.

“We heard Senator Schumer say [the first round of RRF] would be a down payment. And none of us thought that a year later, we would be still talking about that damn down payment and needing the rest of it,” Polmar said.

Beyond current monetary strain, RRF’s absence is also sapping the industry of future potential, she said.

“You can't think creatively. You can't pivot your business. … These folks are beyond exhausted. They're weary,”she said. “Right now all they're doing is thinking about the present and how they're going to make it through the next day.”

We took a look at several market performance indicators over the past year to get a sense of how the absence of RRF impacted U.S. restaurants. And while it’s impossible to know both how far the ripple effects of RRF’s closure reaches — or to what degree the closure exacerbated pain points like inflation and labor shortages — it’s clear the past year was challenging. And some restaurants fear there are more dire consequences ahead.

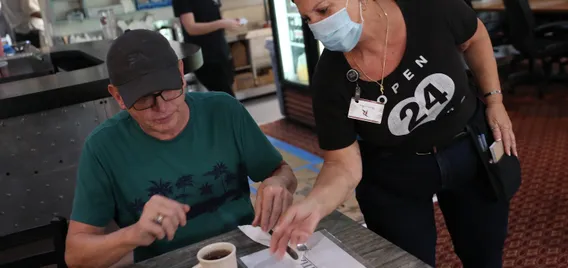

Labor

Openings and closures

Sales