Passport to success: How restaurants can make international expansion work

After a 40-year absence, Wendy’s will finally break back into the European market within the next 12 to 18 months, executives said during its Investor Day in October. The push overseas will begin with a U.K. location, Abigail Pringle, Wendy’s president, international and chief development officer said. Wendy’s will also create an office to run European operations.

Its European expansion is part of the company’s overall plans to boost international sales by $1 billion to $2 billion and reach 1,500 stores abroad, up from 950 units, by 2024, she said. Canada is currently Wendy’s largest international market, but it’s also operating in Latin America and Asia-Pacific/Middle East.

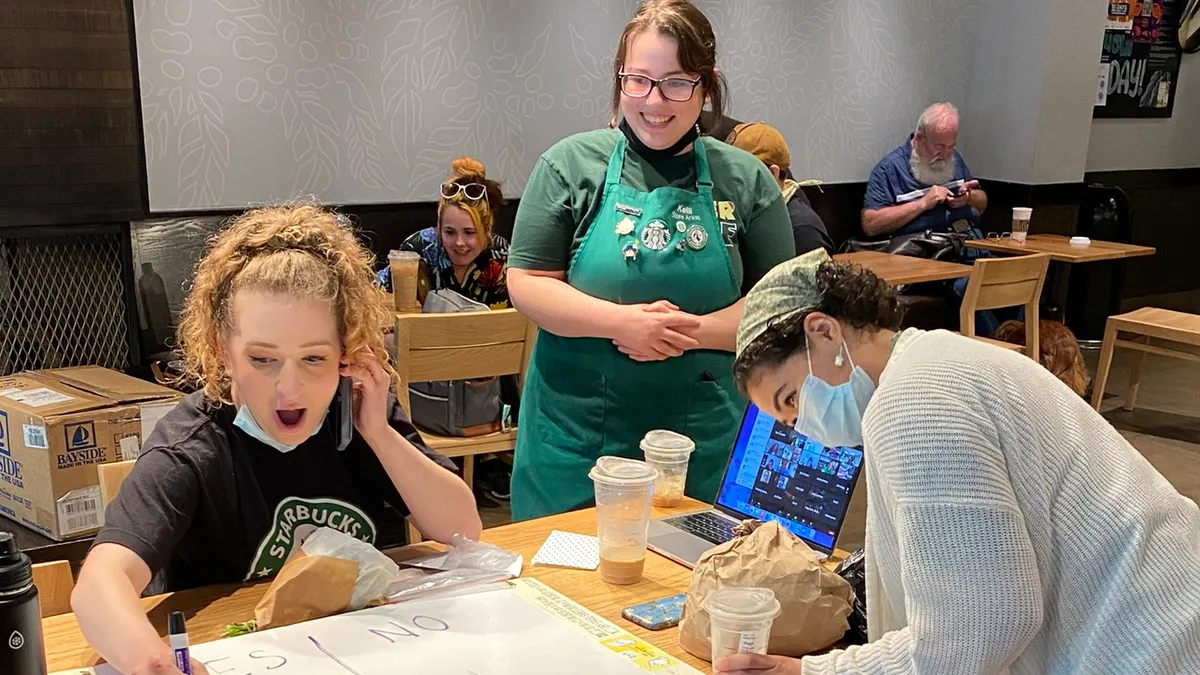

This strategy is reflective of equally aggressive international expansion plans sweeping the QSR space: Starbucks currently has more international stores than it does domestic ones, and China is now KFC’s biggest market, making up nearly a third of its sales during Q2 2019. The Habit Burger, Taco Bell, Popeyes and FAT Brands have also made big development commitments in Asia-Pacific, where demand for American brands remains unabated.

Crafting a successful entry into a new country isn’t easy, however. These expansion plans require months, if not years, of research and oversight as brands search for the right partner to develop a real estate plan and menu that match the market’s demographic. And with so many brands also following the same strategy, expansion means facing a lot of local and international competition.

“You’re starting from scratch in another country,” Edwards Global Services CEO William Edwards told Restaurant Dive. The consultancy has worked with several brands such as Chili’s, Denny’s, Carl’s Jr. to help them expand internationally. “It’s doable. We’ve proven that, but it’s a challenge.”

International isn’t right for all brands

Before expanding overseas, restaurants need to consider the potential of domestic initiatives versus international growth and determine the risk profile and financial return of each to figure out whether it is best to deepen growth in the U.S. or expand internationally, Chris Randall, LEK Consulting managing director and partner, told Restaurant Dive.

“As you expand internationally, there are a lot of risks to consider, distinctive consumer preferences, difficult or more complex regulatory and business environments to navigate,” Randall said. “Of course, there’s entrenched local competition a lot of the time.”

For regional U.S. chains, there may be more room to build out domestically than going abroad, Randall said.

“The opportunity to continue to build out the U.S. is definitely lower risk than looking at some international markets,” he said. “The tipping point that I have seen is when there’s less new regional expansion to be had in the U.S. and you’re more in a … saturation point of development for the U.S., then the international opportunity becomes much more sizable relative to the domestic opportunity.”

Sometimes chains think that they will automatically be successful abroad because the concept did well in the U.S, he said.

“We think [this] is a pitfall of many, many chains that maybe don’t invest the time up front to get their strategic playbook in order around market entry,” Randall said.

Smaller brands, those with less than 200 units, often jump into international before they are ready, Edwards said. Going abroad, however, requires a higher level of training and support. Setting up a supply chain can be more difficult in another country. These brands might not understand that they have to work with a licensee to develop a supply chain, and there isn’t necessarily a Sysco or US Foods available to call like there is in the U.S., he said.

Targeting the right regions

Not all countries are the right fit for brands, either. Given the gross domestic product and the saturation level within other countries, there are about 20 or 25 markets that matter, Randall said.

“It doesn’t mean that you can’t have a good business outside of that, but as you start to think about locations that are going to have 100-plus units, there are not many countries and economies that are going to be above that level,” Randall said.

Two of the largest markets where brands are making big moves are China and India.

“If you look at China, India and Indonesia, that’s over 650 million middle-class people,” Edwards said. “They love U.S. food brands.”

FAT Brands has been growing internationally since it entered Canada in 2006, President and CEO Andrew Wiederhorn told Restaurant Dive. The company entered Asia in 2007 and the Middle East in 2008. He expects to open 10 to 20 units annually in the Middle East and Asia outside of even bigger development deals in the works, making it consistent with its goal of driving 25% of its business from international sales.

But expanding abroad doesn’t happen overnight and can take years, from researching an ideal market to finding the right franchisee partner and development sites.

“It’s very expensive to enter international markets,” Wiederhorn said. “You have to have a whole team, a whole platform. You could spend easily $1 million to $2 million just on overhead on a platform to run [in] Asia or the Middle East or wherever.”

It doesn’t guarantee overall success, either.

For example, Domino’s posted 45% in retail sales growth in China, where it opened 20 stores during Q3 2019, CEO Ritch Allison told investors during an October earnings call. It also opened 17 stores in Brazil during the quarter and is seeing particularly strong growth in Japan and India. But even with its positive growth in these five markets, international comps grew only 1.7% compared to U.S. comps of 2.4% during Q3 2019.

The company is focused on improving international sales, Allison said. Domino’s benefits from having a diversified portfolio of international markets, but there is a mix of markets that are “blowing the doors off” in terms of sales and some that are “a little bit more challenged,” Allison said.

Domino’s pricing strategy is not as compelling compared to competitors in some of its more challenged markets. The issues, including the inability to control in-house cost in places like Norway, has forced it to pull out of some international locations completely. Just last week, the pizza chain announced that it would close operations in Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland.

Often area operators lack the same kind of analytics that are used in the U.S. to address where pricing should be to better compete, but Domino’s is working to fix that, he said. The company has teams working with international franchisees to go through data and provide better analytics, he said.

“I’m optimistic, very optimistic about the long-term success of that international business,” Allison said.

Finding the right partner

It takes a lot of time and resources to amass a robust international portfolio like McDonald’s, FAT Brands, KFC and Domino’s. Opening a restaurant in another country can take up to two years, even after signing the license agreement, Edwards said.

First, brands need to find the right partner for international expansion, which should be a professional business entity with good financial stability that signals they are able to invest and open units, he said. The partner also should have experience running and operating restaurants similar to the brand that is expanding abroad, he said.

Ideally, that partner is typically a multi-unit, multi-brand operator, Edwards said.

Franchisors should also evaluate how well a potential partner knows their local market, Randall said. These licensees should be willing to keep lines of communication open and work closely on development, strategic and marketing plans, he said.

Communication is key, especially since issues are likely to arise, he said. Brands will need to work with a partner willing to pivot strategies to be the most successful, Randall said.

“Nobody wants to teach anybody about restaurants, but I will tell you that some brands [that] don’t conduct enough due diligence on who it is they’re talking to to have granted licenses to companies without food experience,” Edwards said. “And typically, the brand doesn’t really end up getting very well developed.”

Denny’s partnered with experienced operator The Bistro Group three and a half years ago to develop units in the Philippines, Edwards said. The master franchisee also owns licenses for TGI Fridays, Texas Roadhouse, Buffalo Wild Wings and Red Lobster, among others. The company has its own kitchens and commissaries, chicken production facilities and beef ranches and their own distribution system, Edwards said. Denny’s was an attractive addition to The Bistro Group’s lineup because it didn’t have a family dining concept and it ended up rounding out its portfolio, Edwards said.

“They’re kind of the platinum ... candidate that restaurants want,” Edwards said.

For Denny’s, this partnership led to eight units in the Philippines within three years, which is a particularly fast pace, Edwards said.

These multi-unit, multi-brand operators are becoming more prevalent in markets where U.S. brands are quickly developing, such as in Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines and Spain, Edwards said. These operators also are prevalent in the U.K., the Middle East and China, he said. While many of these ideal licensees exist, it can be difficult to get them interested in a restaurant brand.

“You have to make sure they’re interested in growing and that they’re interested in the particular brand you’re working with or taking into the country,” he said.

What an American brand looks like abroad

Part of a relationship with a master franchisee also means figuring out what menu items will best translate to the local demographic without a complete overhaul.

“You don’t want to fully change yourself as you go international because you’ve had success domestically,” Randall said.

Brands will typically allow 10% up to 20% of menu changes based on locality, Edwards said. Oftentimes the restaurant will add local dishes, without dramatically changing the menu, he said. Sometimes an ingredient might just not be available in that part of the world and would need to be swapped out for something else, Randall said.

“Let’s face it. If you’ve got a pork sandwich brand, it’s not going to do very well in the Middle East,” Edwards said.

Outside of offering an LTO or product that might appeal to a local demographic, FAT Brands hasn’t needed to make any significant adjustments to its menus across its subsidiaries, Wiederhorn said.

“Whatever you get in America is what you get in an international market,” Wiederhorn said. “They want that experience. That keeps us competitive.”

For its Buffalo’s Cafe and Express brand, consumers might want spicier sauces, which are already on its menu. It might just highlight those sauces more and downplay the milder ones, Wiederhorn said. For Fatburger, burger size may change depending on the market, like Asia, where people tend to eat smaller hamburgers.

For a brand like Denny’s, it would still have its Grand Slam on an international menu, but there would be different components, Edwards said. When his company helped Denny’s enter the Middle East a few years ago, everything had to be Halal, which is meat prepared based on Muslim law and forbids pork products. That meant turning bacon into beef bacon, he said.

This works because Denny’s has a menu development team that works with the local licensee, and there is also a supply chain quality assurance team that looks for local support or suppliers, Edwards said.

“Smaller brands don’t have that,” Edwards said. “They have to find a licensee that already has that capability, that can source locally.”

Finding local sources that meet quality standards isn’t just challenging for small brands, either. About five years ago, Edwards Global Services helped Carl’s Jr. get into Vietnam, and it took a year to find a beef source that was acceptable in quality and price, Edwards said.

In addition to menu adjustments, brands have to rethink their real estate and design options. While drive-thru may make up a big part of a restaurant’s real estate in the U.S., that might not be viable in other countries, Randall said. Some of these restaurants end up looking more like full-service concepts abroad. The same happened with Carl’s Jr in Tokyo, Edwards said.

Pizza Hut is considered a mid- to high-end sitdown restaurant in Asia, Randall said. This format has gained traction with local consumers, and Asia and China — which Yum divides into separate markets — combined make up 30% of the company’s sales as of Q2 2019, with China and Asia growing 3% and 4%, respectively, year-to-date. Comparatively, in the U.S., Pizza Hut is in the process of closing up to 500 stores and reopening them as fast casual concepts focused on delivery and takeout over the next two years.

A lot of restaurants that are standalones in the U.S. also open in malls overseas because that’s where people go for entertainment and recreation, Edwards said. In the Middle East and Indonesia, malls are popular locations because of the climate and temperature, Edwards said. Consumers, particularly young two-income families, enjoy going to malls because there is parking, air conditioning, it’s safe and everything is available in one place, he said.

Brands also have to take a different approach to technology abroad. Many international markets have better technology than the U.S. does, which can create problems for brands not used to using technology as part of business operations, Edwards said.

In China, for example, cashless pay is popular and apps also are very personalized, Edwards said. So a Chinese consumer expects a restaurant app that knows his/her preferences, Edwards said.

“We’re not there yet in our country. We will get there eventually, but in a lot of countries, especially new markets where the technology’s newer, you either have these things or else you don’t exist,” Edwards said.

Another technology widely used is a web-based real-time tracker that can monitor operations abroad instead of just sending a corporate executive out twice per year to check in on the local licensee, Edwards said. This allows the franchisor to try and fix anything more quickly if it sees a variance, he said.

“[The monitoring] is really paying off with more unit growth per country and more unit sales growth per country because the systems are being followed more carefully,” Edwards said.

Even with the right partner, menu and technology in place, brands should be aware of an eventual saturation point that is starting to hit several international markets. In the short-term, there is still plenty of enthusiasm and demand for American brands.

“It’s going to be awhile before there’s too many, but there are some countries where it’s getting a bit busy right now,” Edwards said.

Indonesia is starting to get saturated, especially with most of its development limited to Jakarta, Edwards said. Mexico and United Arab Emirates also may be hitting capacity, he said. But even with that limitation, people in these countries still want more brands and several restaurants have opened there within the last few years. Shake Shack, for example, opened its first Mexico location during the summer.

International markets still have high density of people to restaurants, a ratio that will remain lower than in the U.S., Randall said. So while saturation may be cropping up in some cities, American brands don’t have to worry quite yet.

“There should be plenty of runway over the next five years,” Randall said.